What is Multiple Sclerosis?

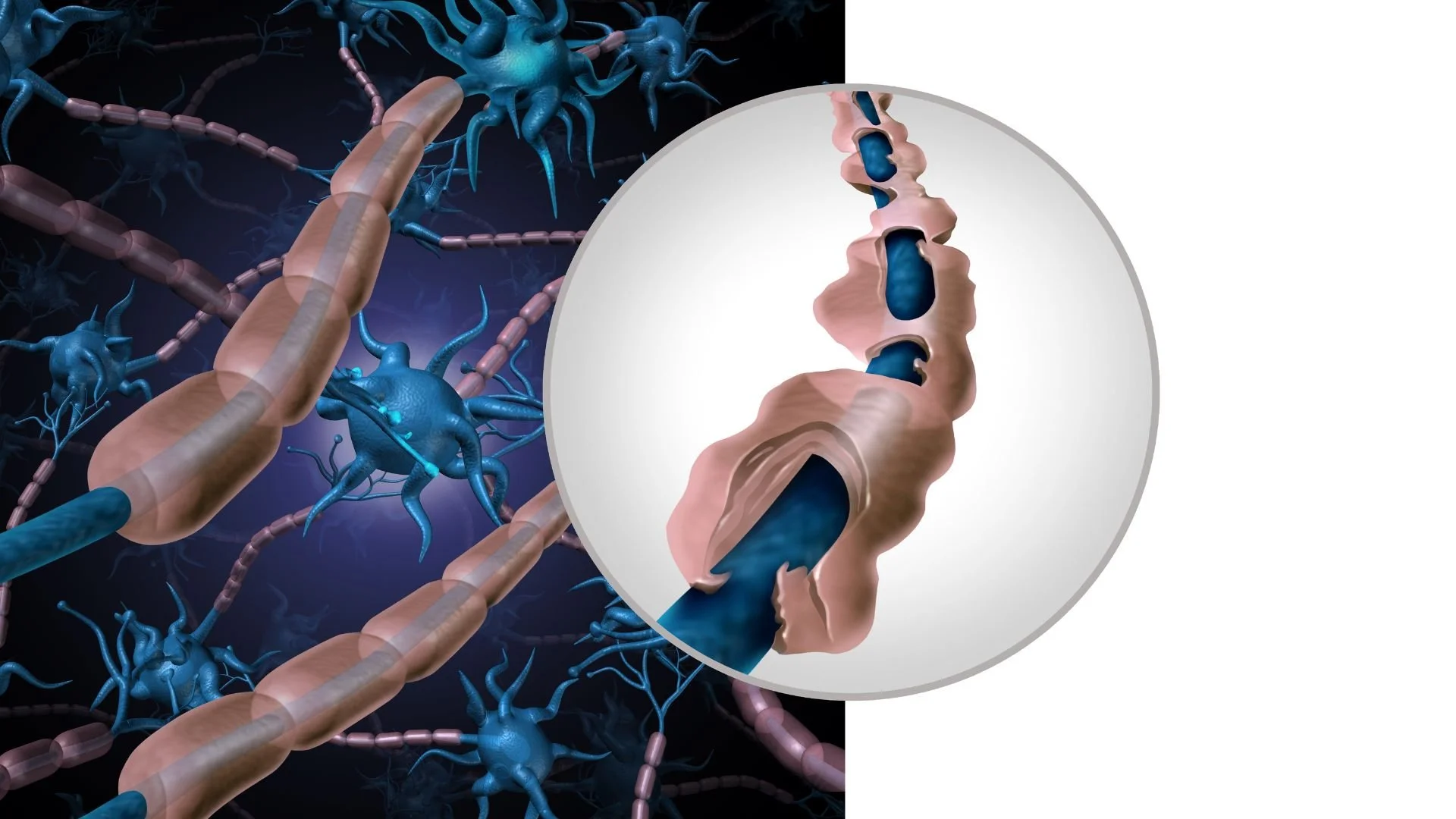

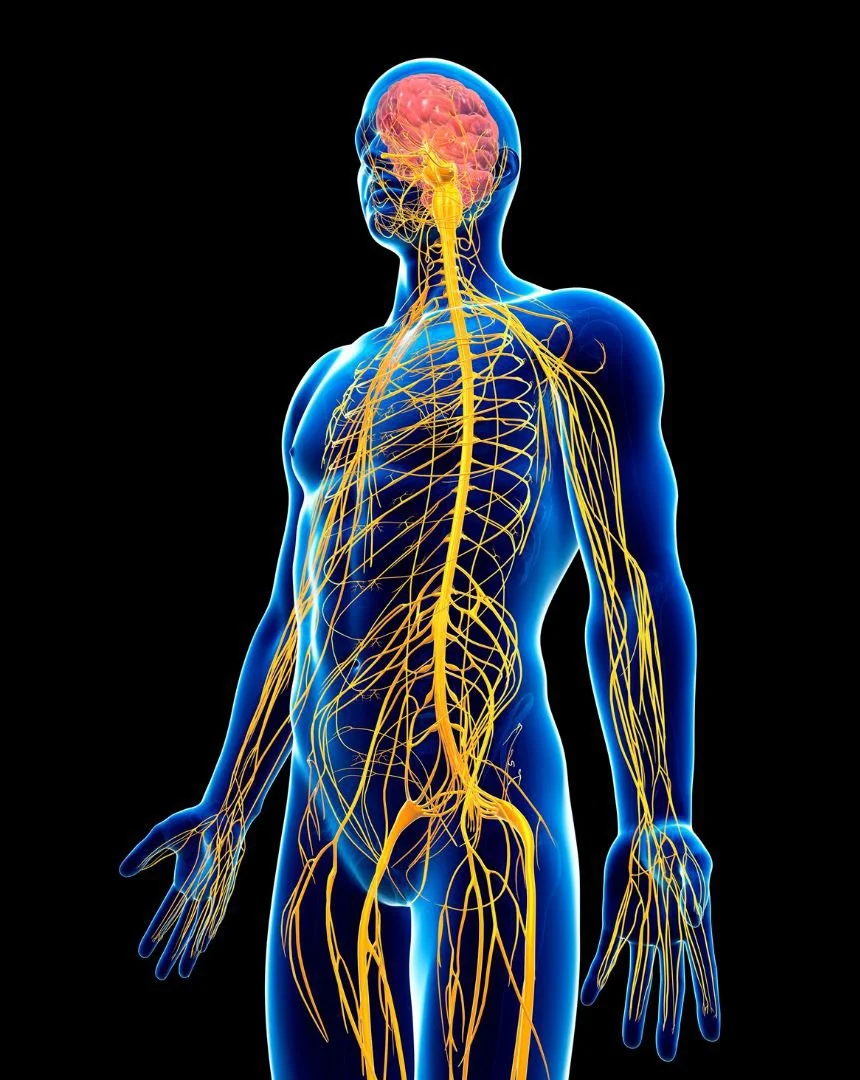

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease of the central nervous system – which includes the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves. In MS, the body’s own immune system mistakenly attacks a substance called myelin, which is the protective sheath covering nerve fibers. You can think of myelin as the insulation around electrical wires (the nerves being the “wires”). When myelin is damaged by these immune attacks, the nerves have trouble transmitting signals. This can lead to a wide range of symptoms depending on which nerves are affected.

MS is considered an immune-mediated or autoimmune disease, meaning the immune system is involved in causing damage. Specifically, certain white blood cells infiltrate the brain and spinal cord and create inflammation that strips away myelin (a process called demyelination). Over time, this can also lead to some permanent nerve fiber damage in addition to myelin loss. The name “multiple sclerosis” actually comes from the scarring (sclerosis) that occurs in multiple areas of the central nervous system due to this demyelination. These scars or lesions can be seen on MRI scans and are a hallmark of MS.

MS affects everyone differently, but it often causes episodes of neurological symptoms – these are called “attacks” or relapses – followed by periods of partial or complete recovery (remission). Because of this pattern, the most common type of MS is known as relapsing-remitting MS. During a relapse, new symptoms appear or old ones get worse, and they last for at least 24 hours (often days or weeks), then improve. In remission, you might feel back to normal or have some lingering mild symptoms. Over years, some people with relapsing MS transition into a phase where the disease steadily worsens with fewer obvious relapses – this is called secondary-progressive MS. There is also a less common form called primary-progressive MS, in which symptoms slowly and continuously worsen from the start, without clear relapses and remissions.

MS most often begins in young adulthood. Typically, symptom onset is between ages 20 and 40, making it a leading cause of neurological disability in young adults. It’s also more frequent in women – women are about 2 to 3 times more likely to develop MS than men. Globally, hundreds of thousands of people live with MS (over 2.8 million worldwide, and nearly 1 million in the U.S.), so it’s not extremely rare, but it’s also not super common. The severity of MS can range from very mild (some people have only occasional symptoms and little disability even decades later) to more severe cases where mobility and daily function are significantly affected. The good news is MS is almost never fatal – most people with MS have a normal or near-normal life expectancy, especially now that treatments are available. It’s not contagious or directly inherited, but as we’ll discuss, there are risk factors that make someone more likely to get MS.

Common Symptoms of MS

Because MS lesions (areas of damage) can occur anywhere in the brain or spinal cord, symptoms can vary widely from person to person. However, there are some common patterns. Often, the first noticeable symptom of MS is something like:

Vision problems: Blurry vision or dim vision in one eye, often with pain when moving the eye. This is called optic neuritis and results from inflammation of the optic nerve. It can cause a partial loss of vision in that eye (usually central vision), often accompanied by eye pain. Double vision can also occur if MS affects the brainstem areas controlling eye movement. Vision issues tend to improve over weeks, but an episode of optic neuritis is a classic MS warning sign.

Numbness or tingling: MS frequently causes numbness, tingling, or “pins and needles” sensations in the arms, legs, face, or trunk. For example, one might feel a numb patch on one side of the body or a tingling in the legs that doesn’t go away. These sensory disturbances reflect nerve signals being disrupted.

Muscle weakness or stiffness: You might experience weakness in an arm or leg, making it hard to grip things or causing a limb to feel heavy when walking. Sometimes there’s accompanying spasticity, which is muscle stiffness or spasms, causing a limb to feel tight or difficult to move. MS can also cause clumsiness or poor coordination – for instance, stumbling more, or feeling unsteady on your feet due to weakness and cerebellar (balance area) involvement.

Difficulty with balance and walking: Because MS often affects pathways in the spinal cord or brain that coordinate movement, people may have trouble with balance. They might walk with a wider gait to steady themselves or feel dizzy. Vertigo (a spinning sensation) can occur if certain brain areas are affected. Over time, some individuals develop a characteristic way of walking due to spasticity (legs stiff) or needing support.

Fatigue: This is one of the most common and debilitating MS symptoms. MS-related fatigue is not just ordinary tiredness; it’s an overwhelming sense of exhaustion that can come on suddenly and isn’t necessarily proportional to activity level. People often find fatigue is worse in the afternoon or in hot weather.

Electric shock sensations: A classic MS symptom called Lhermitte’s sign is a brief electric shock-like sensation that runs down the spine or into the limbs when the person bends their neck forward. It’s due to an MS lesion in the cervical (neck) spinal cord and is a unique, though not universal, symptom.

Bladder and bowel issues: MS can disrupt the nerve signals that control bladder and bowel function. Many patients experience urinary urgency (a sudden need to go) or hesitancy, or incontinence. Constipation is also common, while some have bowel urgency. These issues are often manageable with diet or medication, but can be an annoying part of MS.

Cognitive and mood changes: Some people with MS have mild issues with memory, attention, or multitasking – for example, feeling a bit “foggy” or slower at processing information. Depression and anxiety are also more common in MS, partly because of the disease’s impact on the brain and partly as a reaction to living with a chronic illness. MS can also cause mood swings or irritability in some cases.

Pain: While MS is not classically thought of as a painful condition, it can cause pain. This might be nerve pain like a burning or shooting sensation in the limbs. A notable example is trigeminal neuralgia, which is intense facial pain, and can occur in MS if the trigeminal nerve in the brainstem is affected. Muscle spasms or stiffness can also be painful. About half of people with MS experience some chronic pain.

It’s important to know that no two people with MS have exactly the same symptoms, and symptoms can change over time. During a relapse, symptoms flare up – for example, someone might suddenly have double vision and balance problems for a few weeks. With recovery, those symptoms might partly or fully go away, but another relapse down the line could cause a different symptom, like arm weakness. Over years, there can be residual symptoms that don’t fully disappear after a relapse (for instance, a persistent slight numbness or a mild walking difficulty). In the long term, especially in progressive forms of MS, symptoms like mobility issues or cognitive difficulties can slowly worsen.

Another peculiarity of MS symptoms: they can worsen temporarily with heat or fever. Many patients notice that on hot days or after a hot shower, their old symptoms briefly flare up (e.g., vision might blur again or legs feel weaker). This is called a pseudo-relapse or Uhthoff’s phenomenon – it happens because nerve conduction, which is already impaired by demyelination, becomes even less efficient when body temperature rises. It’s not causing new damage and typically resolves once you cool down.

Given the variety of symptoms, MS can sometimes be tricky to diagnose. But if you experience neurological symptoms like those described – especially in a young adult – and they come and go, doctors will consider MS in the differential diagnosis.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of MS remains unknown, but it’s clear that it involves a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors. Essentially, some people have genes that make their immune system more likely to malfunction and attack myelin, and then some environmental trigger initiates the disease process.

Here’s what researchers know about risk factors and possible triggers for MS:

Genetics: MS is not directly inherited (unlike a single-gene disorder), but having a family member with MS does raise your risk a bit. In the general population, the risk of MS is about 0.3–0.5% (around 1 in 200-300 people). If you have a parent or sibling with MS, your risk might go up to roughly 2-4%. This suggests there is a genetic component. Scientists have identified certain genes (especially those related to immune system regulation, like HLA genes) that are more common in people with MS. However, genetics is only part of the story – clearly, many people with genetic risk factors never get MS, and identical twins, where one has MS, the other often does not. So other factors must play a big role.

Environment (Geography): MS is more common in certain parts of the world. It has a higher prevalence in regions farther from the equator, such as northern Europe, the northern United States and Canada, New Zealand, and southern Australia. Conversely, it’s less common in places like Asia and Africa, and in equatorial regions. One theory is that this pattern relates to sunlight exposure and vitamin D. Sunlight helps our skin produce vitamin D, and people in high latitude climates (with less intense sun) historically had lower vitamin D levels. Low vitamin D is associated with a higher risk of developing MS. In fact, studies have found that people with MS often have low vitamin D levels, and those with higher vitamin D have a lower risk of attacks. This has led many doctors to recommend vitamin D supplementation to people with MS or at risk for MS.

Smoking: Cigarette smoking appears to increase the risk of developing MS and can also make MS progress faster. Smokers who have MS tend to have more lesions and worse outcomes than non-smokers with MS. The reasons aren’t entirely clear, but smoking can affect the immune system and cause inflammation, which might contribute.

Obesity: Some research suggests that being overweight or obese in adolescence is a risk factor for MS later in life. Obesity can cause a chronic inflammatory state and also is linked with lower vitamin D, which may tie into the risk.

Infections – especially Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV): A groundbreaking study in recent years found strong evidence that Epstein-Barr virus (the virus that causes mononucleosis, aka “mono”) is a key trigger for MS. Essentially, nearly everyone with MS has been infected with EBV, and those who never got EBV (which is rare) almost never get MS. EBV might confuse the immune system; one hypothesis is “molecular mimicry,” where parts of the virus resemble myelin proteins, tricking the immune system into attacking myelin after an EBV infection. Other viruses have been studied (like HHV-6, or varicella), but EBV has the strongest link. It’s important to note that EBV infection is super common (most people carry it), so it’s not the sole cause – but it seems to be a necessary factor for most. There is hope that an EBV vaccine in the future might reduce MS incidence.

Other Autoimmune Conditions: If you already have certain other autoimmune diseases (like type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, or inflammatory bowel disease), your risk of MS is slightly higher. This might be because of underlying immune system hyperactivity or shared genetic factors among these conditions.

Age and Sex: As mentioned, MS typically strikes young adults – most often in the 20s and 30s for relapsing MS. Primary-progressive MS often has onset a bit later (40s or 50s). It’s more common in women, especially the relapsing type (likely due to hormonal and genetic immune differences; interestingly, some autoimmune diseases have female predominance, and MS is one of them).

To sum up, the thinking is that a genetically susceptible person encounters a trigger (like EBV infection, possibly combined with factors like vitamin D deficiency or smoking), and this sets off an autoimmune attack on their own myelin. Once the process starts, it leads to the formation of MS lesions and the clinical symptoms we talked about.

It’s worth noting what does not cause MS: it’s not caused by stress (though stress can worsen symptoms), not caused by any known toxin or vaccine or anything like that. There were past theories about things like aspartame or allergies causing MS, but none have panned out. It’s fundamentally an immune-related attack, not something you did wrong.

How is MS Diagnosed?

Diagnosing multiple sclerosis usually involves a combination of clinical evaluation, MRI scans, and sometimes other tests. There isn’t a single “MS blood test,” so doctors rely on a combination of evidence. The goal is to show that there are lesions in the CNS separated in space (meaning in different locations in the nervous system) and time (meaning occurred at different points in time), and no other explanation for them. Here’s how it typically goes:

Neurological Exam and History: A neurologist will take a detailed history of your symptoms – what you’ve experienced, when it started, how it changed – and perform a neuro exam to test your strength, sensation, reflexes, vision, balance, etc. Certain patterns (like an episode of optic neuritis in the past and now weakness in the legs) might already strongly suggest MS. They’ll also ask about any other medical issues, to rule out MS “mimics.” For example, some B12 deficiency or certain infections can cause similar symptoms, so they want to get the full picture.

MRI Scans: MRI is a critical tool for MS. An MRI of the brain and spinal cord can show the lesions or plaques caused by MS. These appear as bright spots on certain MRI sequences. Doctors look for lesions in typical MS areas: the brain’s white matter (often around the ventricles – the fluid spaces), the optic nerves, the brainstem and cerebellum, and the spinal cord. MS lesions vary in size; they could be tiny or quite large. Often, an MRI will show multiple lesions of varying ages (some might enhance with contrast dye, indicating active inflammation, while older ones won’t). If the MRI shows lesions in places characteristic of MS and you have a matching history of attacks, that can clinch the diagnosis. In fact, it’s now possible to diagnose MS after a single clinical attack if the MRI already shows evidence of older silent lesions. MRI has made diagnosing MS much faster and more accurate than decades ago when we had to rely on clinical progression.

Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap): In some cases, especially if the diagnosis is uncertain, a doctor may do a lumbar puncture to test your cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In MS, the CSF often contains oligoclonal bands, which are proteins (antibodies) that indicate an immune response in the spinal fluid. Having oligoclonal bands in CSF supports an MS diagnosis (seen in the majority of MS patients). The spinal fluid is also checked to make sure there’s no infection or other condition (for example, to rule out Lyme disease or neuromyelitis optica which have different markers).

Evoked Potentials: These are specialized tests where they measure how quickly your nervous system responds to certain stimuli (visual, auditory, or electrical on the limbs). For example, a visual evoked potential test can detect a slight slowing of nerve conduction from the eye to the brain, which might indicate past optic neuritis even if you recovered and see normally now. Evoked potentials aren’t done as commonly as MRI and LP nowadays, but they can still provide evidence of lesions that might not be causing obvious symptoms.

Blood Tests: While there’s no MS-specific blood test, doctors do blood work to exclude other diagnoses that can mimic MS. They might test for lupus or other rheumatologic diseases, B12 levels (B12 deficiency can cause demyelination), certain infections, or markers for neuromyelitis optica (NMO) which is a distinct condition often confused with MS but caused by a different mechanism. Essentially, blood tests help ensure nothing else is going on.

The diagnostic criteria for MS, called the McDonald criteria (revised over the years), combine all this information. In practice, if someone has had at least two attacks and MRI evidence of lesions in at least two typical areas, it’s straightforward MS. If it’s one attack, but MRI shows older lesions too, that’s enough now to say MS. If MRI is not classic, sometimes the patient might be monitored over time or need the LP to add more evidence.

Getting a diagnosis of MS can be scary, but it’s also the first step toward getting treatment that can help. And it’s important to get the diagnosis right, because other conditions can look like MS and require different treatments. That’s why neurologists are thorough in the evaluation.

Treatment of MS

There are three main aspects to MS treatment: managing acute attacks, using disease-modifying therapies to reduce future disease activity, and treating the symptoms that MS causes in daily life. We’ll break these down:

Treating Acute Relapses (Attacks): When a person has a significant MS flare-up – for instance, a new weakness or loss of vision that’s disrupting function – doctors often use medications to shorten the attack. The standard treatment is corticosteroids, usually high-dose IV methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol) given daily for a few days. Steroids help reduce the inflammation in the brain and spinal cord, and many patients find their symptoms improve faster than they would on their own. Steroids don’t affect the long-term course of the disease (they don’t prevent future attacks or disability progression), but they can get you through a bad relapse more quickly by hastening recovery. The side effects of short-term high-dose steroids can include insomnia, mood swings, metallic taste, or fluid retention, but these are generally manageable. If a relapse is especially severe and not responding to steroids – for example, if someone has a severe attack causing paralysis – doctors might consider plasmapheresis (plasma exchange). In plasmapheresis, blood is filtered to remove and replace plasma, which can help remove harmful antibodies. It’s typically used in severe relapses of relapsing MS that don’t respond to steroids, and it’s more often helpful in relapsing MS than in progressive MS.

Disease-Modifying Therapies (DMTs): These are long-term treatments aimed at reducing the frequency of relapses and slowing the accumulation of lesions and disability. Over the past few decades, MS treatment has been revolutionized by these therapies. As of 2025, there are over 20 medications approved for relapsing forms of MS. They do not cure MS, but they significantly alter its course. The idea is to keep the immune system from attacking the myelin so often or so intensely. These medications come in different forms: injectable, oral, or infusions.

Injectable medications: The first MS therapies (from the 1990s) were injectables like interferon-beta (with brand names like Avonex, Rebif, Betaferon) and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone). Interferons modulate the immune response and reduce relapses by about 30%. They can cause flu-like side effects initially. Glatiramer is a mixture of proteins that resembles myelin basic protein; it’s thought to act as a decoy for the immune system. It’s also given by injection and tends to have minimal systemic side effects (mostly injection site reactions). These injectables are still used, especially for those who prefer their long track record and safety profile.

Oral medications: In the last 10-15 years, several pills have been approved for MS. For example, fingolimod (Gilenya) was the first oral DMT. It works by trapping certain immune cells in lymph nodes so they can’t get out and attack the CNS. There are others like dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera) and diroximel fumarate (a similar drug with maybe fewer GI side effects), which likely work by shifting the immune system to a less inflammatory state and may have neuroprotective properties. Teriflunomide (Aubagio) is another oral that blocks rapidly dividing immune cells. And siponimod (Mayzent) is a newer oral specifically approved for secondary-progressive MS, similar mechanism to fingolimod. More recently, cladribine (Mavenclad) came as an oral short-course therapy that depletes certain lymphocytes for a while. Each of these has its own risk/benefit profile – for instance, some can affect liver function, blood counts, or carry infection risks. Doctors choose based on disease severity and patient factors.

Infusion therapies: These are given by IV, ranging from monthly to once every 6 months or even less often. They include natalizumab (Tysabri), ocrelizumab (Ocrevus), alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), and others. Natalizumab is a potent drug that blocks immune cells from entering the brain; it’s very effective at preventing relapses but has a risk of a rare brain infection (PML), so its use is carefully monitored and often reserved for more aggressive MS or those who fail other treatments. Ocrelizumab targets B-cells (a type of immune cell) and is given every 6 months; it’s notable for being the first to show benefit in primary-progressive MS as well as relapsing MS. This has been a game-changer, especially for progressive patients who previously had no options. Alemtuzumab is a powerful immune rebooter (it depletes both T and B immune cells) given in two yearly courses; it can dramatically reduce MS activity but carries risks of other autoimmune side effects. Mitoxantrone is a chemotherapy agent rarely used now due to toxicity, but it was an older option for very aggressive MS.

The goal with DMTs is to start treatment early in the disease course, especially for relapsing MS, because evidence shows that early treatment can reduce the long-term accumulation of disability. These medications don’t generally make you feel better immediately (they aren’t for symptoms per se), but you take them to keep the disease calm in the background – fewer relapses, fewer new MRI lesions, and slower progression. Many people on DMTs might go years without a significant relapse, which is a huge improvement from the era before these existed. Doctors will typically monitor with periodic MRIs to ensure the medication is working (no new lesions) and will switch meds if MS is still active. There are now so many options that treatment can be individualized to the patient’s lifestyle and the aggressiveness of their MS.

Symptom Management: Even with disease-modifying therapy keeping the MS under control, people may have persistent symptoms that need treatment. For example:

Fatigue: This can be managed with energy-conserving strategies (naps, cooling vests in heat) and sometimes medications like amantadine or modafinil can give some relief.

Muscle spasticity: Stiffness or spasms in legs can be treated with muscle relaxants like baclofen or tizanidine. For severe spasticity not relieved by oral meds, there are options like botulinum toxin injections or intrathecal baclofen pumps.

Pain: Nerve pain may respond to medications like gabapentin or duloxetine. Trigeminal neuralgia (face pain) can be treated with carbamazepine or other neuropathic pain meds.

Bladder issues: If there’s urgency or overactive bladder, medications such as oxybutynin can help. If there’s retention, sometimes self-catheterization is needed.

Depression or mood issues: Counseling or antidepressants may be appropriate. It’s important to treat these, as depression is common and can greatly affect quality of life.

Tremor or balance problems: These are tough to medicate, but occupational therapy can teach ways to cope (like weights on utensils for tremor).

Cognitive impairment: Cognitive rehabilitation and memory aids (like planners or phone reminders) can assist. Keeping mentally active is encouraged.

Physical and Occupational Therapy: Rehab professionals are key in MS care. Physical therapists help with exercises to maintain strength and mobility, training in using canes or other devices if needed, and techniques to manage fatigue while staying active. Occupational therapists assist in making everyday tasks easier (maybe modifying your home or work setup, teaching energy conservation, etc.). Speech therapists can help if there are speech or swallowing issues.

Exercise: Staying as active as possible is recommended for people with MS. Regular exercise can help with fatigue, improve mood, and maintain muscle tone and cardiovascular health. It might need to be low-impact (swimming is great, also yoga, walking, stationary biking). One key is avoiding overheating during exercise – maybe exercise in a cool environment or with cooling gear, since heat can worsen symptoms transiently.

Assistive devices: If needed, using braces (for foot drop), canes, or other aids can keep you mobile and safe. Some people with MS might use a scooter or wheelchair for longer distances but still walk around the house, for instance. The use of such devices can be just during flares or permanent in later stages – it’s all about maximizing independence and preventing falls.

There are also some newer symptom treatments being explored. For instance, functional electrical stimulation (FES) can help with foot drop by electrically stimulating the nerve to lift the foot during walking. Neuromodulation techniques like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) are being studied for MS fatigue or depression. And for very advanced symptoms, options like deep brain stimulation can be considered for severe tremors.

Crucially, comprehensive care is the approach: an MS patient may have a neurologist for DMTs and relapses, plus a rehab team, plus perhaps a urologist for bladder issues, mental health support, etc. Many MS centers offer a multidisciplinary approach so patients can get all-around care.

Another point – early and continuous treatment with DMTs has significantly improved the outlook for many MS patients. We now talk about the possibility of “no evidence of disease activity” (NEDA) as a treatment goal – meaning no relapses, no new MRI lesions, and no progression on exams. While not everyone achieves that, many do for significant periods. The progression of disability can be slowed dramatically. For example, decades ago, needing a cane or wheelchair 15-20 years into MS was common; now, many patients on modern therapies remain fully ambulatory or only mildly affected even after decades.

Living with MS: It often requires some adjustments, but many people with MS continue working, parenting, and doing their usual activities, especially if the disease is well-controlled. Fatigue might require more resting, and planning ahead for flares or scheduling activities around energy levels helps. It’s wise to avoid overheating and to try to minimize stress (though easier said than done). Connecting with an MS community (like local chapters of the National MS Society, or online forums) can provide support and practical tips.

Outlook for MS

MS is a lifelong condition, but it’s important to know that most people with MS will not become severely disabled. In fact, the majority of MS patients remain able to walk, though maybe with some aid, throughout life. As mentioned, MS rarely affects lifespan significantly; however, advanced MS can indirectly cause complications (like infections from immobility). But with current treatments, the prognosis has improved a lot. Many patients, especially those treated early, experience long stretches of remission and only mild to moderate symptoms. Some even have a relatively benign course with minimal issues.

Researchers continue to work on even better treatments – including potentially repairing myelin (remyelination therapies) and treatments targeting the progressive phase. For instance, there are trials with stem cell transplants (HSCT) that aim to reboot the immune system entirely – some have shown promising results in aggressive MS. There are also new oral meds and infusion treatments in development (e.g., BTK inhibitors, which are another kind of immune-modulating drug, are in trials as of 2025).

The ultimate hope is to find a cure or preventive for MS. While we’re not there yet, each decade has brought more powerful therapies. It’s quite possible that a combination of therapies in the future will halt MS in its tracks or even reverse some damage.

If you’ve been diagnosed with MS, it’s normal to feel anxious about the future. But remember: MS is manageable, and you can live a long, fulfilling life with it. Many people with MS are doing extraordinary things – from writing books to running businesses – sometimes you wouldn’t even know they have it. Taking your medication as prescribed, maintaining a healthy lifestyle (exercise, diet, no smoking, vitamin D, etc.), and having a support network will put you in the best position to thrive. And don’t hesitate to lean on your medical team – they’re there to adjust your treatment as needed and to help you with any new symptoms or concerns that come up.

In summary, multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease attacking the nervous system’s myelin, leading to symptoms like vision loss, limb weakness, numbness, and fatigue. It commonly follows a relapsing-remitting course. Though the cause isn’t fully known, factors like genetics, Epstein-Barr virus, low vitamin D, and smoking play a role. Diagnosis is made via clinical evaluation and MRI (and sometimes spinal fluid analysis). Treatment has three pillars: treat acute attacks (with steroids), use disease-modifying drugs long-term to reduce disease activity (there are many effective options now), and manage symptoms through various medications and rehabilitation strategies. With these approaches, many people with MS are living active lives and the progression of disability can be significantly slowed. Ongoing research continues to bring hope for even better outcomes in the future.

Please note: This information is provided for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your primary care physician or a qualified healthcare provider regarding any questions or concerns about your health. Content created with the assistance of ChatGPT to provide clear, accessible medical condition descriptions.